|

For the Tourism Trade and Visitors to the Drakensberg |

| |

|

Copyright: Cathkin Booking and Management Services

|

| |

|

Common Duiker (Sylvicapra grimmia)

Photo: Pixabay |

| |

|

Winter in the Drakensberg brings a quiet, striking beauty to the mountains. The air is crisp and clear from June to August, with sweeping views of snow-dusted peaks and golden grasslands stretching into the distance. Mornings begin with frost underfoot and a soft light that sets the sandstone cliffs aglow, while daytime skies remain high and cloudless, perfect for walking. Rivers run low, and waterfalls may freeze. Wildlife remains active but more visible, moving through open terrain in the cool air. Evenings are cold and still, ideal for gathering around a fire beneath a canopy of stars. It’s a time of contrast—warm sun, icy shadows, silent valleys, and vast, open skies. In winter, the Drakensberg reveals its more contemplative side, offering solitude, clarity, and moments of quiet awe in its rugged embrace. |

| |

|

“I prefer winter and fall, when you feel the bone structure of the landscape—the loneliness of it—the dead feeling of winter. Something waits beneath it—the whole story doesn’t show.”

— Andrew Wyeth |

| |

|

Contents:

- Drakensberg's Duikers;

- Bannerman's Pass and Langalibalele Pass Loop;

- The Langalibalele Rebellion of 1873 and the Skirmish at Bushman’s River Pass;

- World-renowned personalities associated with the Drakensberg;

- Dating the Drakensberg's San Rock Art;

- A Drakensberg birding list;

- Drakensberg Events;

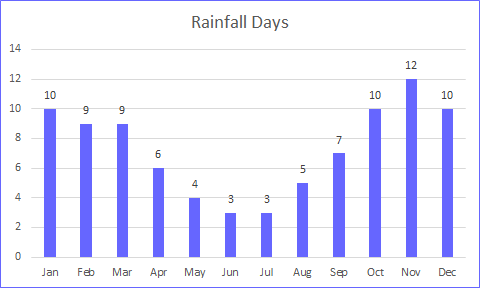

- Weather charts;

- Tourism directory

|

| |

|

Drakensberg's Common Duiker (Sylvicapra grimmia)

|

| |

|

Drakensberg's Common Duiker (Sylvicapra grimmia), also known as the grey duiker, is a small antelope throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa. Compact and agile, it stands about half a metre at the shoulder and weighs between 12 and 25 kilograms. Males typically have short, backwards-curving horns, while females are usually hornless. Its coat varies in colour depending on the region, ranging from greyish-brown to reddish hues, with a distinctive dark stripe down the face and a white underbelly.

Its adaptability allows it to inhabit a wide range of environments. The Drakensberg can be seen in lower montane grasslands, forest margins, and wooded valleys, particularly where there is enough cover for concealment. While it's more common in the foothills and lower slopes than on the high alpine plateaus, sightings are possible throughout much of the range, especially in less disturbed areas. It favours areas with dense cover, which it uses to avoid predators and regulate body temperature. Primarily solitary and shy by nature, it is most active at dawn and dusk, though it may also be seen during the night or on overcast days.

Unlike many other antelope species, the Common Duiker has a broad diet. It browses on leaves, fruits, seeds, flowers, and young shoots, but also consumes insects, small birds, and carrion when the opportunity arises. This omnivorous feeding behaviour supports its success across diverse and changing environments.

Territorial by instinct, duikers mark their ranges with scent glands near the eyes. Males can be surprisingly aggressive in defending their territory from rivals. Breeding occurs throughout the year in many areas, with females typically giving birth to a single fawn after a gestation period of around six months.

Despite localised threats from hunting and habitat loss, the Common Duiker remains widespread and resilient in the Drakensberg, playing an essential role in ecosystems as both a browser and a seed disperser. |

| |

|

Bannerman's Pass and Langalibalele Pass Loop

|

| |

|

The Bannerman's Pass and Langalibalele Pass Loop is one of the most captivating multi-day hiking routes in the Maloti-Drakensberg World Heritage Site, a UNESCO World Heritage Site renowned for its dramatic scenery and cultural significance. Beginning and ending at Giant's Castle Camp, this circular hike takes trekkers through two prominent mountain passes, combining breathtaking views, diverse landscapes, and a powerful sense of history.

A Loop Worth the Effort

Depending on the chosen path, the route typically spans between 26 and 30 kilometres and climbs to more than 2,900 metres above sea level. It can be completed over two to three days, with overnight stops at Bannerman's Hut or Spare Rib Cave near the escarpment. While it's possible to hike this loop in either direction, many ascend via Bannerman's Pass and descend through Langalibalele Pass, allowing for a more gradual and scenic return.

Climbing Bannerman's Pass

Named after a British colonial officer, Bannerman's Pass offers a quieter, more remote alternative to other popular routes in the area. The climb begins on gently sloping paths that rise steadily through montane grasslands, eventually leading to a steeper ascent along rocky ridges. The pass offers expansive views of the Giant's Castle area and beyond.

A great place to break the journey is Bannerman's Hut, a simple stone shelter located near the foot of the pass. It's an ideal base to rest, take in the surroundings, and prepare for the next day's leg.

Descending Langalibalele Pass

Langalibalele Pass is steeped in historical importance. It takes its name from Chief Langalibalele, leader of the Hlubi people, who crossed these mountains in the 1870s while evading colonial authorities. The descent offers expansive vistas across the KwaZulu-Natal interior, lined with the rugged terrain that defines the Drakensberg.

On clear days, you'll enjoy panoramic views across the Bushmen's River valley. Watch for wildlife such as eland, mountain reedbuck, and soaring raptors. You may also encounter rock shelters adorned with ancient San rock art—silent reminders of the area's deep cultural roots.

There is a perfect spot to camp at the base of this camp.

Highlights of the Circuit

Varied Terrain: The trail delivers an ever-changing landscape from grassy slopes and river crossings to high cliffs and rock-strewn paths.

Spectacular Views: The escarpment offers sweeping panoramas in every direction, especially rewarding at sunrise or sunset.

Historical Significance: Walk in the footsteps of the soldiers who fought at the top of this pass in 1873. A detailed account of this battle is provided in the article that follows.

Wild Beauty: This part of the Drakensberg remains untouched, offering solitude, clean mountain air, and a rich diversity of plant and animal life.

Guided by James Seymour

This hike is a guided experience by James Seymour, a seasoned mountain guide with extensive knowledge of the Drakensberg's environment and heritage. His leadership ensures a well-paced, safe journey with added insights into the area's geology, wildlife, and human history.

James's approach blends adventure with interpretation, turning a physical challenge into a deeper connection with the landscape.

Planning Essentials

Duration: Best completed over 2–3 days

Difficulty: Suitable for fit and experienced hikers

Accommodation: Bannerman's Hut or wild camping in shelters such as Spare Rib Cave on or near the escarpment

Essentials: Proper hiking boots, layered clothing, rain gear, food, water, and navigational tools

Weather: Conditions can change rapidly—always prepare for wind, rain, and cold

Why Choose This Loop?

The Bannerman's–Langalibalele Pass Loop is ideal for hikers seeking a longer, more immersive experience in the Drakensberg. It offers the satisfaction of a circular route, the contrast of two distinct passes, and a mix of natural beauty and historical depth. Whether you're after solitude, scenery, or a sense of connection with South Africa's past, this trail delivers.

Start Your Journey

To book a guided hike or learn more about this route, get in touch:

james@cathkinmanagement.com

|

| |

|

Click on the above image for a larger version of the route map. |

| |

|

Bannerman's Hut and Bannerman's Pass |

| |

|

Camp Site at the base of Langalibalele Pass |

| |

|

The Langalibalele Rebellion of 1873 and the Skirmish at Bushman’s River Pass

|

| |

|

Langalibalele: Chief of the amaHlubi |

| |

The Langalibalele Rebellion of 1873 was a pivotal event in South African history, highlighting the tensions between the British colonial authorities and indigenous African leaders over issues of autonomy, resource control, and firearm possession. Central to this conflict was the skirmish at Bushman’s River Pass (Langalibalele Pass), where colonial forces suffered a significant defeat due to poor planning, navigational errors, and the strategic advantage held by the amaHlubi warriors.

Background to the Rebellion

Langalibalele, the hereditary chief of the amaHlubi people, was born around 1814. In 1849, he and his people settled in the British colony of Natal after fleeing conflicts with the Zulu kingdom. The British, particularly Theophilus Shepstone, welcomed the amaHlubi as a buffer between settler communities and other indigenous groups.

Tensions arose in the early 1870s when many amaHlubi men travelled to work in the diamond fields of Kimberley—some acquired firearms, which they returned to Natal as part of their remuneration. In 1873, the colonial administration, led by Resident Magistrate John Macfarlane, ordered Langalibalele to register these firearms. However, Langalibalele refused, citing his inability to account for all weapons possessed by his people. His refusal was perceived as defiance, leading Lieutenant Governor Sir Benjamin Pine to declare the amaHlubi in rebellion.

The Skirmish at Bushman’s River Pass

In response to Langalibalele’s perceived rebellion, Major Anthony William Durnford was tasked with leading a military force to capture him. Expecting confrontation, Langalibalele and his followers sought refuge in Basutoland (modern-day Lesotho) via the Bushman’s River Pass.

Navigational Error and the Nhlawathimbe Pass

A critical mistake was made when the colonial troops were guided up the wrong route—Nhlawathimbe Pass instead of Bushman’s River Pass. This pass was steeper and more treacherous, causing delays and leaving the troops exhausted by the time they reached the summit. The amaHlubi, well-acquainted with the terrain, had already taken strategic positions at the top. This error placed the colonial forces vulnerable and contributed to the following disaster.

Failure of the Second Section Under Captain Albert Alison

To strengthen the operation, a second section of colonial forces was deployed under the command of Captain Albert Alison. This column attempted to climb a pass near Champagne Castle, another part of the Drakensberg range. The objective was to find a suitable crossing point and link up with Durnford’s main force to trap Langalibalele and his followers.

However, this attempt failed. Captain Alison’s troops could not find a viable pass through the rugged and steep terrain. As a result, they could not rendezvous with Durnford’s forces, leaving them isolated and without reinforcements at a critical moment. This failure significantly weakened the colonial strategy and contributed to the disastrous outcome of the skirmish.

The Ambush and Colonial Losses

On November 3, 1873, Durnford’s forces encountered a large assembly of amaHlubi warriors at the top of the pass. Initial attempts to negotiate failed, and the situation quickly escalated into violence. The amaHlubi, some armed with firearms from the diamond fields, ambushed the colonial troops. Five members of the colonial force were killed, and Durnford himself was seriously wounded, sustaining injuries that left his left arm permanently impaired.

The Fallen Soldiers

The skirmish at Bushman’s River Pass resulted in the deaths of several colonial troops, including:

Trooper Robert Henry Erskine – Son of Major Erskine, the Colonial Secretary, who was assisting Major Durnford at his death.

Trooper Edwin Bond – A member of the Royal Natal Carbineers, killed in the initial attack.

Trooper Charles Davie Potterill – Another Carbineer who fell during the skirmish.

Interpreter Elijah Nkambule – Killed while serving as an interpreter for the colonial forces.

Interpreter Katana – Another interpreter who lost his life in the engagement.

These casualties highlighted the serious miscalculations made by the colonial forces and their underestimation of the amaHlubi resistance.

Aftermath and Consequences

Following the failed operation, the British intensified their efforts to capture Langalibalele. By December 1873, he was apprehended and subjected to a controversial trial, which was widely criticised for procedural irregularities. He was convicted of rebellion and sentenced to life imprisonment on Robben Island. However, due to public outcry, he was released in 1875, although he remained under restrictions until he died in 1889.

The rebellion had profound consequences for the amaHlubi people. The colonial government dismantled their settlements, confiscated cattle, and dispersed the community, effectively breaking their societal structure. Additionally, Fort Durnford was constructed in Estcourt in 1875 to prevent future indigenous uprisings.

The Langalibalele Rebellion and the skirmish at Bushman’s River Pass reflect the broader struggles between indigenous leaders and colonial authorities in South Africa. The rebellion was rooted in disputes over land, autonomy, and firearm control, while the battle highlighted the challenges of enforcing colonial rule in rugged terrain. The navigational error at Nhlawathimbe Pass, the failure of Captain Albert Alison’s section to find a suitable pass near Champagne Castle, and the underestimation of the amaHlubi’s military capability all contributed to the disastrous outcome for the colonial forces. The events of 1873 stand as a testament to the complexities of colonial expansion and the resilience of indigenous resistance.

The amaHlubi originated in the central regions of southern Africa, with their early roots believed to be in what is today southern and central KwaZulu-Natal and parts of the Eastern Cape. Oral traditions and historical evidence suggest that they are part of the broader Nguni ethnolinguistic group and were long-established in the Drakensberg foothills and interior highlands before the disruptions of the early 19th century.

The amaHlubi had a distinct identity and a well-organised chieftainship system. They were not Zulu, although over time they came into contact with powerful neighbouring groups, including the Zulu kingdom under Shaka. In the early 1800s, during the period known as the Mfecane (a time of widespread upheaval, warfare, and migration across southern Africa), the amaHlubi were displaced by the Zulu and other rising powers.

Around 1820–1830, the amaHlubi migrated westward into the Natal Drakensberg region under increasing pressure from the expanding Zulu kingdom. Their leader at the time, Chief Matiwane, moved the people into what would later become Basutoland (Lesotho) and the eastern Free State, but their dispersal continued. After Matiwane's death, the amaHlubi came under the leadership of Langalibalele, who in 1849 led a group of his people to settle peacefully in Natal, under British protection, in the Estcourt–Bushman’s River area.

In summary, the amaHlubi originated from precolonial southeastern Africa, were displaced during the Mfecane, and eventually settled in Natal under colonial rule, where tensions eventually led to the 1873 rebellion.

|

| |

|

World-renowned personalities associated with the Drakensberg

|

| |

|

Princess Elizabeth, King George VI and Princess Margaret at Royal Natal |

| |

|

The Maloti-Drakensberg World Heritage Site, straddling the border between South Africa and Lesotho, is one of southern Africa's most culturally and environmentally significant landscapes. Its sheer cliffs, rock shelters adorned with ancient San paintings, and sweeping vistas have left an enduring impression on all who have visited. Among them are several renowned personalities—writers, leaders, royals, and musicians—whose lives intersected with the Drakensberg in meaningful ways.

J.R.R. Tolkien and the Landscape of Legend

Although J.R.R. Tolkien left South Africa as a child, the land of his birth—Bloemfontein and its surrounding interior—has long been cited as a potential early influence on his creative imagination. The dramatic forms of the Drakensberg, which rise along the southeastern edge of the interior plateau, bear a striking resemblance to the landscapes described in Tolkien's works, particularly the Misty Mountains. While no direct reference ties Tolkien to the Drakensberg, the similarities have prompted lasting interest in the connection between South African geography and his mythological storytelling.

A Royal Visit to the Mountains

1947, South Africa welcomed the British royal family on a historic tour. As part of their itinerary, King George VI, Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother), and the young Princess Elizabeth—who would become Queen Elizabeth II—visited the northern Drakensberg, staying at Royal Natal National Park. They admired the grandeur of the Amphitheatre, one of the range's iconic formations.

They were accompanied by Jan Smuts, South Africa's Minister at the time, a man with a deep appreciation for botany and the natural environment. Smuts, a soldier-statesman and philosopher, had a personal affinity for South Africa's traditions and often spoke of the spiritual significance of the natural world. The royal party helped draw international attention to the Drakensberg as a place of beauty and symbolic importance.

A Choir in the Clouds: Mandela and the Drakensberg Boys

The Drakensberg Boys Choir School, established in 1967 in the Champagne Valley, has long been one of South Africa's youth music institutions. In 1995, during commemorations marking the 75th anniversary of the South African Air Force, the choir performed at a remote mountaintop venue near Cathkin Peak. The occasion was made more memorable by President Nelson Mandela, who arrived by helicopter and met the choir following their performance. The moment was a poignant reflection of post-apartheid South Africa—youthful voices echoing through ancient mountains, witnessed by the president who had helped usher in a new era of freedom.

Mohandas Gandhi and the Battlefields near the Drakensberg

During the Anglo-Boer War, Mohandas Gandhi—not yet known as Mahatma—lived in South Africa and formed the Indian Ambulance Corps, a voluntary medical unit composed of Indian residents. In January 1900, this unit assisted British forces during the Battle of Spion Kop, one of the most infamous battles of the war, which took place near the northern foothills of the Drakensberg.

Though Gandhi may not have been physically present on the battlefield, historical records confirm that he and his corps operated in the surrounding area. The experience had a profound and lasting impact on Gandhi, influencing his ideas about service, duty, and nonviolence. During this period, the foundations of his later leadership began to form.

Mandela and the Mountain as Metaphor

Although Nelson Mandela did not spend extensive time in the Drakensberg, the mountains stood as a powerful metaphor in his life. Mandela often spoke of struggle as a climb, famously saying, "After" climbing a great hill, one only finds that there are many more hills to climb." The"Mandela Capture Site, located near Howick in KwaZulu-Natal, lies not far from the central Drakensberg, connecting his journey to the region's historical landscape. |

| |

|

Mohandas Gandhi, before he became Mahatma |

| |

|

Dating the Drakensberg's San Rock Art

|

| |

|

San Rock Art image of a hippopotamus or rain animal, Talana Museum. An excellent example of an early fine line phase San Rock Art image. Possibly as old as 8,000 years. |

| |

Dating San Rock Art can be difficult. San rock art is dated using several scientific methods. The primary techniques include:

Radiocarbon Dating – This method is used when organic materials, such as charcoal or plant fibres, are present in the paint. Scientists measure the decay of carbon isotopes to estimate the age of the artwork.

Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) – This technique determines when quartz grains in surrounding sediment were last exposed to sunlight, helping to establish a timeframe for when the rock art was created.

Uranium-Series Dating – Calcium carbonate deposits that form over or beneath the paintings can be analysed for uranium decay, providing an approximate age range.

Amino Acid Racemisation – If organic binders are present in the paint, this method assesses the breakdown of amino acids over time to estimate the artwork’s age.

Comparative Dating – Researchers analyse the style, layering, and themes of the paintings, comparing them to known archaeological evidence to establish a relative chronology.

Using these methods, some of southern Africa’s oldest known San rock art dates back over 25,000 years. The dating of the Drakensberg San Rock Art has revealed that this art may be as old as 8,000 years before present in the Southern Drakensberg and 3,000 BP in the Central and Northern Drakensberg.

Aaron Mazel developed a stylistic framework to categorise the rock art of the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg region, aiding in understanding the chronological sequence of the artworks. While specific dates for each phase are challenging to ascertain due to the limitations of direct dating methods, Mazel’s framework, combined with advancements in dating techniques, provides approximate timeframes for each stylistic phase.

Mazel’s Stylistic Phases and Associated Dates

Early Fine-Line Phase: Characterised by detailed, thin-line monochromatic depictions, primarily in dark reds and maroons, primarily of human figures and animals. The paint appears stained into the rock surface, with some antelope and human figures conforming to this style. This phase dates back to approximately 3,000 to 2,000 years ago.

Developed Fine-Line Phase: Characterised by bichrome (dull red and white) images, this phase includes human figures and animals in shades of red, with some figures outlined in white. This phase likely occurred around 2,000 to 1,000 years ago.

Late Fine-Line Phase: Marked by increased abstraction and symbolic imagery, possibly reflecting more profound spiritual or ritualistic significance. Characterised by shaded polychrome paintings. This phase showcases more complex compositions, such as the shaded polychrome eland found in Eland Cave. This phase is estimated to have occurred between 1,000 years ago and the 19th century.

Very Late Phase: Characterised by less refined figures, often overlapping older artworks, and possibly influenced by interactions with other cultures. Some of these paintings were created as recently as the late 19th century.

It’s important to note that these dates are approximate and based on current research methodologies. Advancements in dating techniques, such as radiocarbon dating of organic materials associated with the paintings, continue to refine our understanding of the chronology of Drakensberg rock art.

Techniques Aaron Mazel Used to Date Drakensberg Rock Art

Superimposition Analysis – He studied layers of paintings where newer images were painted over older ones to establish a relative chronology.

Stylistic Analysis – By comparing different painting styles and subject matter, he identified artistic trends and estimated their timeframes.

Ethnographic Comparison – He used historical records and San oral traditions to interpret the meanings of the paintings and estimate their age based on cultural continuity.

Direct and Indirect Dating Methods – Although direct radiocarbon dating of pigments was difficult due to mineral-based paints, he collaborated with other researchers to use dating techniques such as oxalate accretions and radiocarbon dating of organic materials in nearby archaeological sites.

Archaeological Context – He correlated rock art with excavated materials from nearby rock shelters to estimate when the paintings were likely made.

Mazel’s work significantly contributed to understanding San rock art’s social, spiritual, and historical significance, placing some paintings at least 3,000 years old, possibly dating back to 8,000 years.

|

| |

|

Late Fine Line, Therianthropes Procession. eSibayeni. |

| |

|

A comprehensive list of birds in the Drakensberg has been created using information from various sources, including the Wildlife and Environment Society of South Africa, Birdlife South Africa, and Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife. The plan is to update this list regularly as the names of bird species change and provide a link for all future issues of the Drakensberg Times. The table indicates common and notable bird species in the Drakensberg. Click on the following link - Drakensberg Bird List. |

| |

|

EVENTS in the CATHKIN PARK, WINTERTON and NORTHERN DRAKENSBERG

Winterton parkrun takes place every Saturday morning from the Waffle Hut starting at 08.00. Register on www.parkrun.co.za/winterton Cannibal Cave parkrun, which takes place in the Northern Drakensberg.

Cathkin Park Walking Group takes place every Tuesday. 8.00 in Winter and 7.00 in Summer. Contact Nick 0794936424

Central Drakensberg Hiking Group Saturdays and overnight hikes. Contact James Seymour for details. 0829255508.

Cathkin Park Community Projects Run takes place on the First Friday of the month at 17.00 in Summer and 16.30 in Winter at The Nest. (April to September).

Drakensberg Boys’ Choir School has a concert on Wednesday afternoons during term times www.webtickets.co.za or 0364681012 or 0785118680.

Mountain Music Club takes place on the last Saturday of every month, from 5 pm, usually at Mac’s Café, Cedarwood Shopping Centre. Dave: 0724839049.

27th June: Night Golf VS Agri Show Grounds. In aid of the NG Kerk. Wikus 0828842850

28th June: Drakensberg Polar Bear Swim Challenge at Dragon Peaks, Belinda 0797377282

28th June: Lutheran Bazaar 10.00- 12.00 Winterton Lutheran Church

15th– 17th July: Adventure Reflections. Northern Drakensberg Venue TBC

19th July: Soap Box Derby. Central Drakensberg Venue: TBC. Contact Hester 0615380904

26th July: LOCKK Riders at Winterton Country Club. Contact Aubrey 0732631885

9th Aug: Ntabamoya Trail Run www.kzntrailrunning.co.za

5th– 7th Sept. Mont Aux Sources Ultra Trail Run. 55km and 20km www.montauxsourcesultratrail.co.za

5th - 6th Sept: The Berg Show at VS Agri Grounds R74 Joanine 0828564368

11th-15th Sept: Fibre Festival at Ardmore Guest Farm 0762670969

19th– 21 Sept: Berg Birding with Andrew Weaver. Cavern Berg Resort.. 0837015724

4th Oct: Run the Berg. All Out Adventures www.runtheberg.co.za

25th – 26thOct: Kudu Canter contact tamsyn@kuducanter.co.za

1st Nov: Winterton Street Market. Winterton. Contact 0825489910

5th – 7th Dec: Christmas in the Berg at the Drakensberg Boys’ Choir School. www.dbchoir.com

Ann Gray

|

| |

|

Drakensberg's Weather Charts |

| |

|

Drakensberg Tourism Directory |

| |

|